Read this story in Nepali: घ्याङफेदी-कोलकाता कनेक्सन : गाउँबाट हराएका दिदीबहिनी एउटै कोठीमा

Rimaya (name changed), who was studying in Grade 6 at a school in Ghyangphedi, Nuwakot, stopped coming to school. When she did not return even after 15 days, the teachers and friends went to her house. But the 13-year-old was not at home.

This was in the Nepali month of Magh of 2079 BS (January/February 2023). When asked about Rimaya, her parents would reply, “She has gone to a relative’s house.” However, the same Rimaya was found two years later, in March 2025 (Chaitra, 2081 BS), at the Shanti Brothel, located on Lane No. 15 of Sonagachi, Kolkata, India. From there, a team from Maiti Nepal rescued her and brought her back to Nepal.

This was in the Nepali month of Magh of 2079 BS (January/February 2023). When asked about Rimaya, her parents would reply, “She has gone to a relative’s house.” However, the same Rimaya was found two years later, in March 2025 (Chaitra, 2081 BS), at the Shanti Brothel, located on Lane No. 15 of Sonagachi, Kolkata, India. From there, a team from Maiti Nepal rescued her and brought her back to Nepal.

Sonagachi is known as one of the largest red-light areas in Asia. Rimaya is not the only one trafficked from Nepal to India for the purpose of sexual exploitation. According to the Human Trafficking Investigation Bureau, a total of 149 women, 20 girls, and adolescents from Nuwakot were rescued from India during the five-year period from the fiscal year 2075/076 to 2081/082 (mid-2018 to mid-2025). They have filed cases stating that they were victims of trafficking. During this period, 1,020 cases were registered, involving 2,163 perpetrators.

Rimaya’s own biological elder sister has also reached Sonagachi. Bishwa Khadka, Executive Director of Maiti Nepal, stated that although they knew she was there last year, they were unable to rescue her. “We identified her last year. When we went to investigate and raid the place twice, she was hidden and we couldn’t find her,” says Khadka.

Representatives of organizations working against human trafficking can only raid the brothels in coordination with the Kolkata police. “Sometimes the operations fail when information is leaked,” he explains.

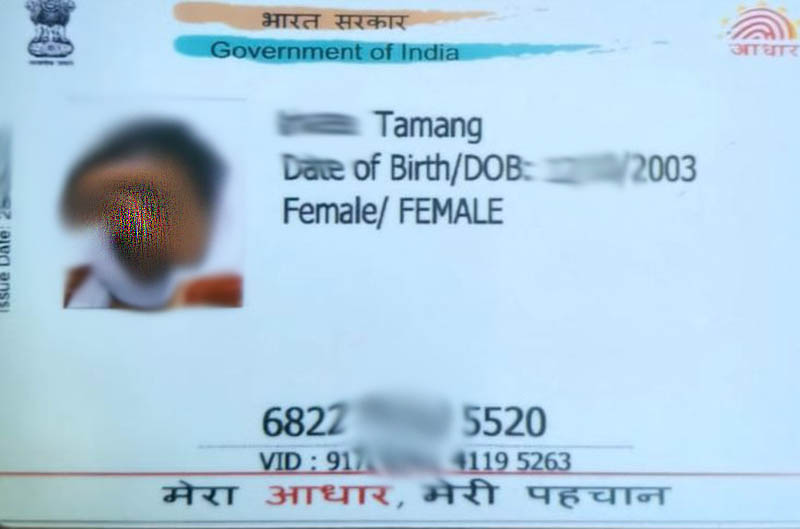

Rimaya is also the latest evidence that siblings are being trafficked into the same brothel and that Nepali girls are being put into the sex trade in Sonagachi brothels after having their identities changed. When the Maiti Nepal team, along with the Indian police, reached Shanti Brothel to rescue Rimaya, the brothel operator showed them an Indian Aadhaar card where her name and age had been changed.

On that card, not only her name but also her date of birth was different. According to the birth registration certificate issued by the then Village Development Committee (VDC) in Nuwakot, her date of birth is 2067 BS (2010/2011, month and date withheld for privacy). The Indian Aadhaar card, which featured her photograph and was issued when she went missing from Nuwakot at the age of 12, turning 13, listed her birth year as 2003, making her nine years older.

In a conversation with the girl, conducted in the presence of a child counsellor coordinated by Maiti Nepal, she described the sexual exploitation of women and girls in the brothel. As a minor, she was sexually exploited from the very day she arrived at the brothel. She was forced to have sexual relations with many people. If she refused, she was physically assaulted. She was not spared even when she was sick.

According to Bishwa Khadka, Executive Director of Maiti Nepal, it had only been six months since her sister was taken to the brothel when they rescued her. “We tried to rescue the two sisters at once,” he said, “But we could not.”

Despite enduring a painful life in the brothel, Rimaya had requested the rescue team not to search for her elder sister. The reason was that the sole source of income for Rimaya’s family was the earnings from the brothel.

Since her family had no other source of income, her father supported them by working as a laborer. At a time when it was difficult for the family of five to make ends meet, two people related to her as aunts/paternal female cousins persuaded her that if she went to India and worked, she would earn money and the family’s situation would improve. Rimaya, who followed these two individuals and ended up in a brothel in India, says she did not know she was being taken to a brothel at first.

However, Rimaya says that after reaching the brothel, she realized that they had also brought other women and girls from the village to various brothels in Kolkata. No complaint has been lodged with the police yet against those who trafficked Rimaya. Rimaya says that both of them are currently out of contact.

According to Sub-section 1 of Section 3 of the Human Trafficking and Transportation (Control) Act, 2064 BS, no one shall be subjected to trafficking or transportation. Sub-section 5 of Article 39 of the Constitution of Nepal, concerning fundamental rights, also states that no child shall be illegally trafficked or transported.

Left studies to end up in a brothel

Two years have passed since two 15-year-old girls, who were studying in Grade 6 at another school in Ghyangphedi, went missing from the village. Four years have passed since another 14-year-old and a 16-year-old, who was studying in Grade 8, went missing from the village.

On Baisakh 17, 2082 BS (April 30, 2025), we visited the same school and inquired about these girls with the teachers and local residents. However, not only the teachers but also no one in the village agreed to talk about this matter.

No complaint has been lodged with the police regarding these girls who went missing from the village. According to organizations working for the prevention of human trafficking, girls who go missing from here are found to have been taken to Kolkata, India, as well as Goa.

According to Naveen Joshi, Executive Director of Kin India, an Indian organization working in the field of human trafficking prevention, Nepali girls and adolescents are taken to brothels, flats, and apartments in Kolkata's Sonagachi, Delhi, Mumbai, and Pune and forced into the sex trade.

According to Bishwa Khadka, Executive Director of Maiti Nepal, girls and adolescents who go missing from Ghyangphedi are found there. “They are sent to cities like Goa under the name of ‘tourism package’,” he says. “These girls and adolescents are taken to wherever the client desires to provide service.”

According to him, some women from Dupcheshwar Rural Municipality-1, Ghyangphedi, who were trafficked to the JB Road, Kolkata brothels under the lure of employment, were later found operating brothels themselves and continuing in the same profession.

After women and girls started disappearing from Ghyangphedi, Adara Development Nepal started a program to retain girl students in schools. To encourage girl students, provisions were made for uniforms, textbooks, free meals, snacks, and accommodation for their studies up to the higher secondary level. However, the girls and adolescents still did not stay in school. “The program was run in the school with the idea that daughters must be educated to stop the trafficking there but it still could not be stopped,” said Prahlad Dhakal, Executive Director of Adara Development Nepal. According to him, a student studying law in Grade 12 at Ghyangphedi School even dropped out of her studies and went to India.

According to Executive Director Prahlad, taking the daughters of those villages to brothels for employment is considered quite normal. He says that even when the location of the girls is identified, they cannot be rescued. “No complaint has been filed with the police,” he says, “Nor have any efforts been made to bring them back.”

According to Prem Syangtan, Headmaster of Ghyangphedi Secondary School, the school is trying to prevent the girls and adolescents from going to India. Attendance in school is mandatory. If a girl does not come to school for one day, teachers go to her house to inquire. However, Prem is saddened that they have not been able to stop them. “Due to fear and terror, the guardians do not speak,” he says. “If we speak, our own lives are in danger.”

It is found that most criminal gangs involved in human trafficking and transportation include close relatives or known acquaintances. According to Nagendra Kunwar, Spokesperson for the Human Trafficking Investigation Bureau, victims hesitate to file a complaint because taking legal action might negatively affect them. He says, “The situation there is no different.”

In many cases, traffickers lure and take children and adolescents to India with the consent of the family or by gaining the willing agreement of the girls themselves. Advocate Somnath Luitel states that even if consent is obtained from the victim in a trafficking case, it is still recognized as a crime.

The Palermo Protocol also defines trafficking as the recruitment, transportation, transfer, harboring or receipt of persons, by means of the threat or use of force or other forms of coercion, of abduction, of fraud, of deception, of the abuse of power or of a position of vulnerability or of the giving or receiving of payments or benefits to achieve the consent of a person having control over another person, for the purpose of exploitation.

Trafficking thriving due to lack of social awareness

A study conducted by Uttam Prasad Upreti, a student at Aalborg University in Denmark, in 2014, based on eight villages in Sindhupalchok and Nuwakot, mentions that human trafficking has flourished due to low social awareness regarding the issue. It reveals the fact that challenging geographical conditions, socio-economic pressure on families, and the normalization of trafficking have made smuggling easier.

According to the data from the former Child Welfare Committee, 15 adolescents from Sindhupalchok and Nuwakot were sold to brothels in Uttar Pradesh and Mumbai, India, following the 2072 BS (2015) earthquake. As per the committee's data, five adolescents brought to India for sale were rescued from Nuwakot.

A joint study by UNDP and the Cultural Research Center also found that 7 out of 10 villages in Nuwakot are active in human trafficking. According to data from the Education Branch of Dupcheshwar Rural Municipality, the school dropout rate among children was 10% last year.

According to 2079 BS (2022/2023) data from the Nuwakot Education Development and Coordination Unit, the dropout rate at the secondary level is 14%. According to a 2023 United Nations report, the rate of trafficking is higher in Nuwakot, Makwanpur, Dhading and Sindhupalchok compared to other districts.

Made to work in a hotel before being taken to India

Two months ago, a 14-year-old girl from Ghyangphedi, Dupcheshwar Rural Municipality-1, stopped attending school after experiencing daily quarrels with her stepmother. Her mother entrusted her to a relative in the village. The relative got her a job at a hotel in Dhunche, Rasuwa. Maiti Nepal rescued her based on information that she was at risk of trafficking. Bishwa Khadka, Executive Director of Maiti Nepal, says that even after informing her parents, they did not come to collect her, so she was placed in a shelter home.

According to him, in recent times, girls and adolescents from Nuwakot are also being trafficked to hotels in Rasuwa and Kathmandu. He claims that they are taught how to work there and then taken to brothels and flats in India for sex work.

Makuri Tamang, Vice-Chairperson of Dupcheshwar Rural Municipality, says that although they ran programs against human trafficking to stop girls and adolescents from going missing in Ghyangphedi, they have been unsuccessful.

Sub-section 1 of Section 6 of the Children's Act, 2075 BS (2018), states that no child should be separated from their parents against their will. Due to poverty and lack of awareness, there are situations where their own families have to hand them over to traffickers. Sub-section 2 of Section 15 of the Act states that every child shall have the right to receive compulsory and free basic-level education and free secondary-level education in a child-friendly environment, as per the prevailing law.

After the country adopted federalism, the District Women and Children Office and the District Child Welfare Committee were dissolved. In the past, those offices used to monitor children's homes, create mechanisms to stop illegal trafficking, and perform other related duties. With those offices dissolved, the Local Government Operation Act, 2074 BS (2017), has entrusted the local levels with the responsibility of protecting children.

Vice-Chairperson Makuri says, "A Child Protection Officer has also been appointed for the protection of children, but it has not been successful." According to her, families here have started seeing their daughters as a source of income. It has not been possible to change the mindset of the parents either. "If anyone in the village inquires or files a complaint, their life is at risk," says Vice-Chairperson Makuri. "Nevertheless, we are monitoring the girls and adolescents."

She also states that the absence of a police post in Ghyangphedi is a problem. Although the Nuwakot District Police Office recommended the establishment of a police post in Ghyangphedi, the local and provincial governments have not implemented it. Vice-Chairperson Makuri states that they are prioritizing the issue of establishing a police post in the area.

Please adhere to our republishing policy if you'd like to republish this story. You can find the guidelines here.